February 14, 2021

Introduction

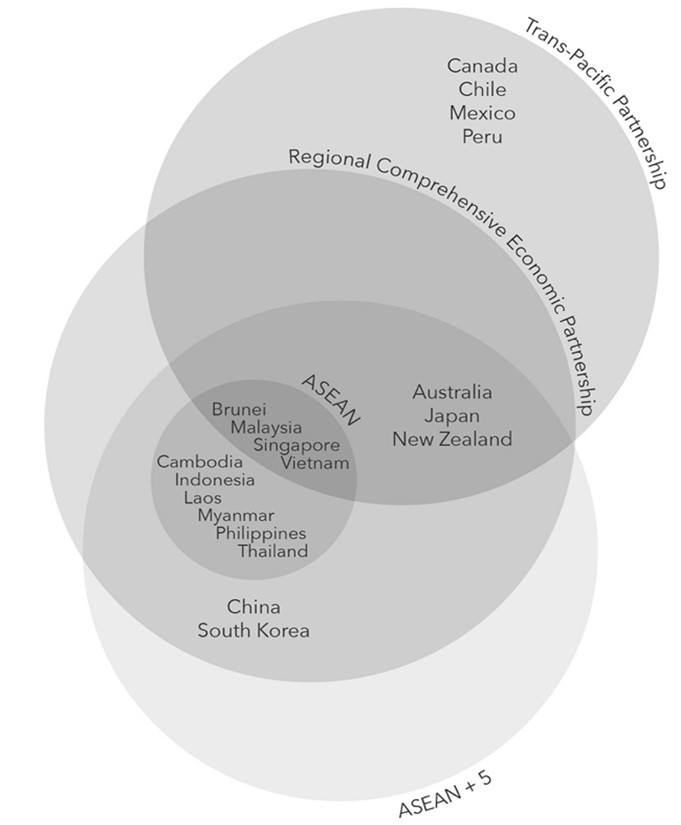

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement was signed on November 15, 2020. It is to date the world's largest trade and investment agreement compromising almost 30% of global GDP (i.e. USD 26.2 trillion) and one-third of the world population. While India stepped out of the negotiation of the Agreement in November 2019, the RCEP counts 15 contracting parties composed of the Association of Southeast Asian Nation (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) and five of ASEAN;s free trade agreement partners (Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea).

The size of RCEP is remarkable, creating the largest trade bloc (before North America and the European Union (EU) and the second-largest investment bloc (after the EU). The pact reflects that the centre of gravity in economic governance is shifting more and more to the Asia-Pacific region without the participation of the United States. Both RCEP and the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which was concluded in 2018, have no Euro-American involvement. Therefore, RCEP is not yet another free trade agreement but an instrument of geopolitical and geostrategic significance. It is a blow to the United States that withdraw from the CPTPP and further consolidates the trends of regionalism and decreasing centrality of the World Trade Organization (WTO). In terms of coverage and depths of commitments, however, the RCEP is less significant, leaving many topics for later implementation. The Agreement also comes with potential legal challenges, such as overlapping commitments for the countries of the Asia-Pacific region increasing the complexity of the region's economic integration.

To grasp an idea of the impacts of the RCEP for international economic law governance, this blog post looks at why the RCEP has been pursued, how it contrasts with the CPTPP, how it reshapes existing and future trade relations and lastly if and how it relates to the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

Asia-Pacific Regionalism

At the start of the RCEP stands ASEAN. Its member states have originally proposed in 2011 that a comprehensive trade agreement would bring all ASEAN key partners under one agreement. The RCEP Agreement had thus not been a China-led project but is evidence of ASEAN's success in managing to place itself at the heart of its region.

As illustrated in the graph, RCEP unites five countries that have concluded FTAs with ASEAN (so-called ASEAN+1 agreements). The graph also reveals that the RCEP's membership partially overlaps with the CPTPP. For Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam, RCEP are between China and Japan and between Japan and South Korea. China already has an FTA with South Korea in place, which was concluded in 2015. In numbers, this means that of the USD 2.3 trillion in good flowing between signatories in 2019, 83% passed between those countries that already have a trade agreement in place. Therefore, economic forecasts predict that China, Japan and South Korea are likely to benefit more from the pact than other RCEP signatories thanks to their newly established trade relationships.

RCEP does not replace any of the existing treaties, including FTAs and international investment agreement (IIAs) that the contracting parties concluded amongst them. In Article 20.1(1) of the agreement, the contracting parties reaffirm the rights and obligations contained in any of the existing international agreements concluded between them. However, other than providing for a consultation mechanism between partied to address potential inconsistencies (Article 20.2), the RCEP does not offer other interpretive guidance. As a result, navigating through different FTAs and IIAs may be a significant challenge. Especially, the entangling of the IIA- network through the replacement of some of the old-generation bilateral investment treaties (BITs) could have been a way forward under the RCEP.

Much Ado About Nothing:

While the size of RCEP is impressive, the coverage of the commercial flow promoting provisions of the Agreement is lacking the same ambition. RCEP is namely less comprehensive compared to the CPTPP. Therefore, the impact of the RCEP can be expected to be weaker in shaping international economic rules and global regulatory governance than it is the case for the CPTPP. For most of the following key issues of international economic law, RCEP sets a framework rather than the last word on the topic:

- Trade in goods: RCEP does not deliver significant new market access for goods in terms of tariff reduction and elimination. As mentioned before, most RCEP parties already have existing FTAs in force with each other through bilateral or plurilateral agreements (i.e. ASEAN+1 FTAs and the CPTPP).

- Rules of origin: The RCEP provides for certain common rules, such as harmonizing the information requirements and local content standards for businesses to be eligible to the preferential terms of the Agreement. The RCEP is expected to facilitate sup-ply-chain management within the region to a significant extent.

- Trade in services: The RCEP establishes ruled for the supply of services including obligations to provide access to foreign service suppliers (market access), and to grant national treatment and most-favoured nation treatment.

- Investment RCEP's investment chapter contains traditional investment protection standards. It contains provisions on investment facilitation and prohibits performance requirements on foreign investors. The RCEP does not provide for investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) but includes a built-in work agenda, which will start no later than two years after the Agreement's entry into force and will consider whether to amend RCEP to include ISDS. This approach seems to reflects a new trend regarding ISDS. Indeed, the very recent conclusion of the negotiations of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) between the EU and China (30 December 2020) also includes a commitment by both sides to pursue the negotiation s on investment protection and investment dispute settlement within two years of its signature.

- Electronic commerce: The RCEP covers commitments on cross border data flows and provides for a more conducive digital trade environment. It limits the scope for governments to impose restrictions including requirements to localize data (Article 12.14).

- Intellectual property (IP): The RCEP seeks to raise standards of IP protection and enforcement including non-traditional trademarks and a range of industrial designs. RCEP parties, which have not yet done so, commit to accede to international IP treaties (Article 11.9). On geographical indications (GIs), parties must adopt or maintain transparency obligations and due process with respect to its domestic legal framework on the protection of GIs.

- Government procurement: The RCEP parties commit to publishing laws, regulations and procedures regarding government procurement, while cooperation provisions set out a mechanism to facilitate consultation and exchange of information.

Lastly, one should note that certain key issues are not covered. Different than the CPTPP or other recent comprehensive FTAs, the RCEP does not contain provisions on labour rights and environmental standards. In sum, the main legal difference between RCEP and CPTPP, is the depth of commitments. This distinctiveness lies within the different reasons why the trade deals have been pursued in the first place. With the former TPP, the United States intended to write the rulebook of trade in the 21st century. Consequently, the Agreement contains a more ambitious regulatory agenda. In contrast, hereto, the RCEP, initiated by ASEAN reflects the "ASEAN way", which consists of the group's non-interventionist principle based on consultation and consensus.

Reshaping International Economic Law and Governance

RCEP - as other comprehensive trade agreements - are not just about increasing economic gains they are geopolitical. The US pull back from the CPTPP was already a marker of waning America influence in the Asia-Pacific region. Today, the conclusion of RCEP with the participation of the US biggest economic rival, China, means further weakening of US leadership. If the United States under the Biden administration decides to rejoin the CPTOO, the United States could counter China's influence. In this respect, the share of CPTPP, which currently represent about 15% of world GDP, would increase to 40% if the United States are a party.

It is tautological but still important that the conclusion of the RCEP is a further step in the process of regionalization. Regional trade blocs are shaping international economic law governance into groups of geostrategic areas reflecting increasing competition and disagreement on trade and investment of the world's leading economies. A telling example is the so-called "China clause" in the recent USMCA. According to Article 32.10 USMCA, any of the parties may terminate the Agreement if another enters into a trade agreement with a :non-market economy". The continuing consolidation of regionalism ultimately deepens the fragmentation of the WTO-based global trading system. Following numerous regional trade agreements, which have created various trading regimes and tariff schedules. This has increased the complexity and transaction costs of cross-border commerce compared with a truly global trading system.

Outlook on the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA)

The AfCFTA Agreement will create the largest free trade area in the world if one measured the size only by the number of countries participating. The pact connects 1.3 billion people across 55 countries. Currently, the AfCFTA is only around 4% of global GDP (African countries have a combined GDP valued at USD 3.4 trillion, compared to USD 26.2 trillion of RCEP countries). Nonetheless, both the RCEP and the AfCFTA can be seen as a momentum for a new 'Bandung' where African and Asian states would build stringer synergies in integrating their economies and would shape new standards in international economic governance that are more adapted to their developmental needs and goals. In this sense, RCEP could be an opportunity for the revival of more South-South cooperation in a post - COVID 19 era and for less reliance on standards exported from the developed world.

Makane Mbegue is a Professor of International Law at the Faculty of Law of the University of Geneva

Stefanie Schacherer is a Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) Post doctoral Research Fellow at World Trade Institute, Berne.